Why Are Foreign Powers Allowed to Influence K-12 Education?

Federal law requires universities to disclose foreign funding. K-12 schools don't. The gap has allowed foreign powers to spend untold millions shaping American education—without parents' knowledge

In 2018, a Washington law firm working for the Turkish government appeared at school board meetings in California, Louisiana, and Massachusetts. Their mission: influence what happened inside approximately 160 American charter schools. They were paid at least $1.8 million to do it. And remarkably, this was all completely legal.

Unregulated Foreign Influence on K-12 Schools

Between 2015 and 2018, the Washington-based law firm Amsterdam & Partners LLP appears to have conducted a coordinated campaign across multiple states on behalf of the Turkish government, the Jewish Onliner has learned. Registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act as #6325, the firm received at least $1.8 million from Ankara to target approximately 160 American charter schools with alleged ties to exiled Turkish cleric Fethullah Gülen.

The campaign’s scope extended beyond traditional lobbying. Amsterdam & Partners met with the heads of school boards and teachers unions, disseminated materials at school board meetings, and attended at school board meetings in California, Louisiana, and Massachusetts. The firm requested meetings with politicians in 26 states (including governors and attorneys general), hired state-level lobbyists, engaged with American media, and conducted congressional lobbying.

The firm also met with the Los Angeles Unified School District Board, the Anaheim Union School District, and other national education organizations, according to its filings with the Justice Department. In September 2019, firm founder Robert Amsterdam spoke at a Turkish government-organized panel at the U.S. Congress.

Yet the campaign raised a fundamental legal question: Should foreign governments be permitted to influence American K-12 education at all? And if the answer is no, what federal requirements currently exist to prevent it? The answers — or lack thereof — reveal both a significant oversight in federal law and a system that tolerates what should be intolerable.

The Disclosure Gap

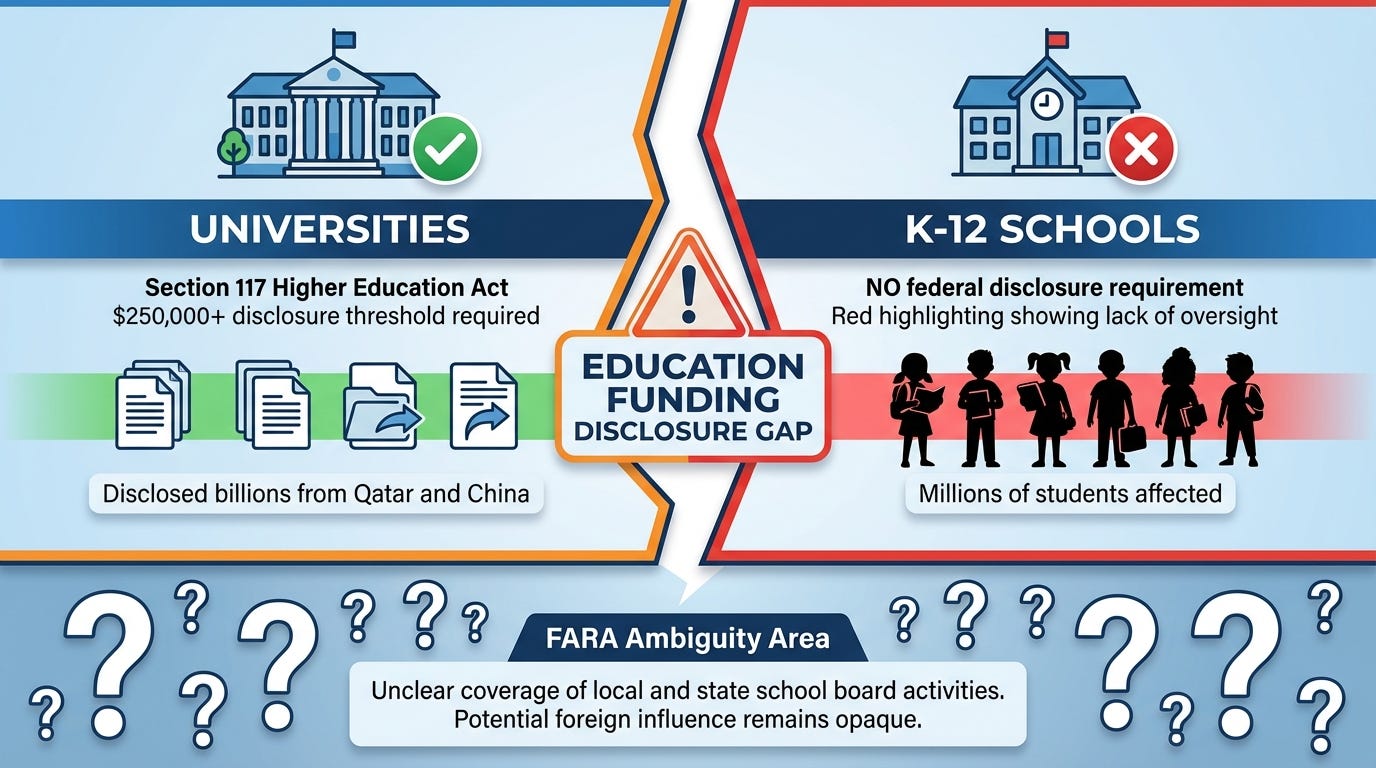

While universities operate under Section 117 of the Higher Education Act, which requires disclosure of foreign gifts exceeding $250,000, K-12 schools and school districts face no equivalent obligation.

Foreign governments and their agents can fund curriculum development, compensate teachers, provide training materials, and shape educational content for millions of American children without having to report it to the federal government. In practice, this means foreign powers have freer access to American kindergartens than to American universities.

The Qatar Foundation International Pattern

The Amsterdam case provides one data point. A second documented case, reported by Jewish Onliner and others, demonstrates how Qatar Foundation International (QFI) has funded American K-12 classrooms to the tune of well over $32 million.

QFI’s activities included funding Arabic language programs, sponsoring teacher training, and co-sponsoring workshops for Brown University’s Choices Program, a curriculum used in approximately 8,000 schools across all 50 states, reaching over one million students, according to the The Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy (ISGAP). QFI reorganized from a nonprofit to a limited liability company in 2012, which ended public disclosure requirements for the organization’s activities and funding sources. In other words, a foreign government-linked entity was able to escape transparency requirements through a simple corporate restructuring—and continued shaping curriculum for American children without public accountability.

Jewish Onliner Report: Qatar's Foreign Influence in American K-12 Classrooms

A new Jewish Onliner report exposes how Qatar Foundation International (QFI) has established an extensive funding network that reaches over one million students in all 50 U.S. states. The organization operates through Arabic language programs, teacher training initiatives, and curriculum development.

Detection Through Circumstance, Not Regulation

Both cases share a characteristic that raises broader questions: they were identified through external investigations and media scrutiny rather than through systematic federal monitoring. The FARA database lists hundreds of active registrants representing countries with documented interests in American education.

Their filings often contain general descriptions such as “educational outreach” or “cultural programming” that could encompass K-12 activities. Without mandatory disclosure requirements or systematic monitoring, federal authorities lack the tools to determine whether other foreign agents are conducting similar campaigns in American schools. More fundamentally, authorities lack the legal framework to prevent these campaigns from occurring in the first place.

Legislative Response and Limitations

In December 2025, the House passed three bills addressing aspects of foreign influence in K-12 education. The TRACE Act would require schools to disclose foreign funding to parents upon request. The CLASS Act would ban certain Chinese-government-linked funding arrangements and require federally funded K–12 schools to report qualifying foreign funds and contracts to the U.S. Department of Education. The PROTECT Act would cut federal funding to schools with Confucius Institute partnerships.

These bills make meaningful progress on transparency and accountability. However, multiple watchdog groups have argued that they remain incomplete. The TRACE Act relies on parental initiative—schools disclose only when asked, placing the burden of vigilance on families who may not know what questions to ask. The CLASS Act and PROTECT Act are principally aimed at countering Chinese state influence, while other foreign-government-linked efforts may still fall outside their core prohibitions and enforcement focus. And critically, all three bills accept the premise that some foreign government involvement in K-12 education is acceptable—they merely seek to manage it better.

More fundamentally, none of these measures expand FARA to explicitly cover K-12 activities, none establish proactive federal disclosure requirements comparable to Section 117's higher education mandate for all foreign countries, and none address the structural loopholes that allow foreign entities—like Qatar Foundation International—to reorganize as LLCs and escape public reporting obligations.

And even if these bills were expanded, they still would not address why foreign states should have a pathway into K–12 classrooms at all.

Open Questions

Several critical questions remain unanswered: How many foreign influence operations in American K-12 education remain undetected? What is the annual flow of foreign funding into schools? How often do curriculum changes occur without parental knowledge? How effectively does FARA capture school-level activities by registered foreign agents?

But the most fundamental question is whether transparency measures—however robust—are an adequate response to foreign government involvement in educating American children. Concerned citizens have noted that it’s unacceptable that foreign governments should have any influence or impact or ability to fund K-12 education at all. Better disclosure may tell us what’s happening, but it doesn’t resolve whether it should be happening in the first place.

These questions persist not from inadequate government effort, but from structural gaps in the regulatory framework.

The result is not intentional concealment but systemic invisibility. Foreign influence in K-12 education cannot be tracked, measured, or evaluated at scale because no legal requirement compels the collection of this data. Until K-12 receives disclosure requirements equivalent to higher education, the scope of foreign influence in American schools will remain largely unknown. And until policymakers confront the question of whether such influence should exist at all, transparency reforms will remain incomplete solutions to a problem that may require prohibition, not disclosure.