New Report Traces How “Foreign Coup” Narrative Helped Deflect Scrutiny From Iran’s Crackdown

Report alleges that IRGC-affiliated messaging on X used viral “proof tokens” to frame unrest as foreign-directed, gaining reach through influencers more than official channels

A new report by the Network Contagion Research Institute (NCRI) and the University of Miami Frost Institute for Data Science and Computing (IDSC) argues that as anti-regime protests spread across Iran, state-aligned outlets and affiliated online networks promoted a counter-narrative portraying the unrest as a foreign intelligence–backed operation rather than a domestic uprising. The report says this attribution framing circulated widely on X and, by shifting blame outward, could reduce scrutiny of the government’s crackdown.

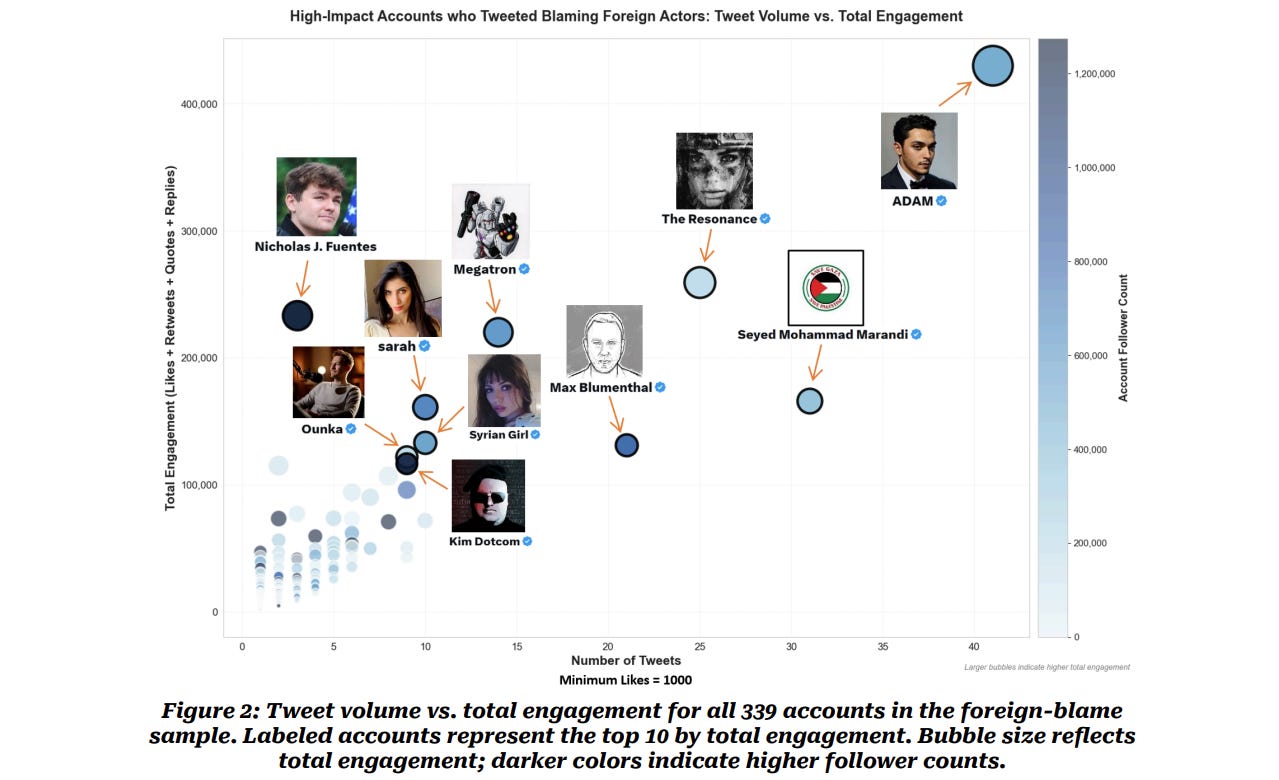

The report, titled “Attribution Warfare: How the Woke Left, Fake MAGA and the IRGC Reframed Iran’s Massacre as a Foreign Coup,” focuses on engagement dynamics on X and claims the regime’s attribution narrative traveled furthest through high-impact influencers rather than official state outlets alone. In the report’s telling, the online campaign did not merely defend the government. It sought to remove agency from protesters by portraying them as instruments of Mossad, the CIA, or a broader foreign coalition, and to reframe state killings as a security response to outside subversion.

A Domestic Uprising Met With Repression

The report places the start of the unrest on Dec. 28, 2025, describing a rapid expansion of protests driven by domestic economic and governance grievances. It says the state’s response escalated quickly, with arrests and deadly force used against demonstrators.

Rather than treat the unrest as a crisis of legitimacy, the report argues, the regime and IRGC-aligned media moved to define it as an external attack. That shift matters, the authors contend, because attribution is not a neutral debate over causality. It can function as a political weapon that changes how violence is perceived. If protests are “foreign-backed,” repression becomes “defense.” If protesters are “agents,” killings become “counterterrorism.”

The report frames this as a modern form of propaganda optimized for social platforms, where a simple explanation can travel faster than detailed reporting and where ambiguity can be weaponized as “proof.”

The Two Viral “Proof Tokens”

The report highlights two social media moments it says were repeatedly treated as evidence of covert foreign involvement.

The first was a Dec. 29 post from an X profile claiming to be Mossad’s official Farsi-language channel, expressing solidarity with protesters. According to the report, the wording was quickly repurposed by regime-aligned accounts as an implicit admission of Israeli operational presence. The authors argue the post became useful not because it offered new intelligence but because it could be circulated as a screenshotable “receipt” that anchored a preferred story line.

The second was a Jan. 2 post by former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo that included a rhetorical line about “every Mossad agent walking beside” Iranians in the street. The report says that remark was treated by aligned commentators as corroboration and became a second shareable token that made the narrative feel confirmed through repetition.

In the report’s framing, this is how attribution warfare works online. Claims do not need to be proven in the investigative sense. They need only a small number of high-visibility “artifacts” that can be reinterpreted as admissions and recycled across networks.

A Blame Narrative That Traveled Through Unlikely messengers

The report’s central contention is that the most consequential distribution did not come solely from Iranian state outlets. It came from a convergence of influencer ecosystems that, while ideologically opposed, amplified the same core attribution claim.

The report labels three broad clusters: IRGC-aligned voices, what it calls the “Woke Left,” and what it calls “Fake MAGA.” It argues the foreign-coup framing fit pre-existing worldviews in each cluster, making it easy to repeat. For some progressive anti-interventionist accounts, the claim aligned with long-standing skepticism of U.S. and Israeli covert action. For a right-branded ecosystem described as inauthentic, the claim aligned with conspiracy politics and grievance-driven narratives about Western intelligence. For regime-aligned channels, it served a direct political purpose: shifting blame away from Tehran for the crackdown and onto external enemies.

In a news context, the report’s most pointed implication is not about ideological hypocrisy. It is about effect. The report argues that when Western-facing influencers echo state-aligned attribution claims, they can help sanitize a government’s use of force by reframing it as a response to foreign sabotage.

Peak Engagement as Protests Escalated

The report links spikes in foreign-blame content to key moments during the unrest. It describes increased traction after Jan. 2 and a larger surge as protests intensified in early January, with the biggest engagement peak around Jan. 12.

It also argues that state messaging and online influencer amplification reinforced each other. As state-aligned outlets described “foreign-backed riots” and highlighted pro-government demonstrations, influencers circulated the same framing as a kind of crowd-sourced “debunk” of the protests.

What the Authors Say Their Data Shows

Methodologically, the report says it collected X posts using an Iran-focused query paired with foreign-actor and geopolitical keywords, then restricted analysis to high-engagement posts, defined as those with at least 1,000 likes. It says a large language model classifier was used to label blame attribution and isolate posts that framed the unrest as foreign-directed.

The report does not present its findings as a measure of public opinion. It presents them as an account of how a particular narrative moved through the most visible part of the platform. Its warning is that regimes facing internal revolt can pair repression with attribution campaigns that shift culpability outward, and that the most effective megaphones may be influential accounts abroad, not government spokespeople at home.