West Point Legal Scholar: Rewrite "Attribution Rules" to Hold Iran Accountable for Proxies

A new U.S. Naval War College study recommends updating international attribution standards to hold states accountable for proxy groups through factual indicators like training and financing

A newly published legal study warns that Iran has systematically exploited weaknesses in international law to escape responsibility for the actions of the militant groups it supports across the Middle East — and offers detailed recommendations to close those loopholes.

Released by the U.S. Naval War College’s Stockton Center for International Law Studies, “Iran and Its Proxies: Attribution and State Responsibility” was authored by Dr. Jennifer Maddocks, a law professor at West Point and fellow at the Lieber Institute for Law and Warfare. Her analysis concludes that the international system’s rules on state responsibility were written for a bygone era of conventional warfare and now fail to address the realities of modern proxy conflicts.

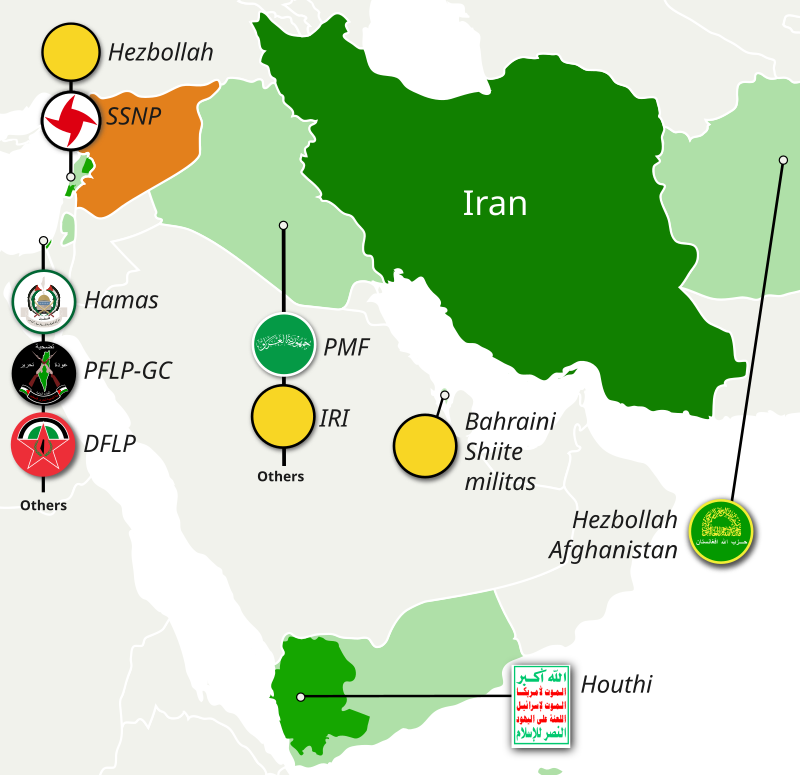

Maddocks argues that current attribution rules in international law make it difficult to pin state responsibility on Tehran for the conduct of proxies including Hezbollah in Lebanon, Shi’a militias in Iraq and Syria, Hamas in Gaza, and the Houthis in Yemen. She writes that “ambiguities surrounding the precise links that exist between Iranian officials and members of a proxy group complicate the attribution analysis and raise doubts regarding the degree of State influence over the acts at issue,” and concludes that, as a result, “international law provides little incentive for Iran to cease its longstanding practice of acting via proxy.”

At the core of her analysis are the International Law Commission’s Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (ARSIWA). Under Articles 4, 5, and 8, a state’s liability turns on whether wrongful conduct can be attributed to it—because the actor is a state organ, has been empowered by law to exercise public functions, or acted under the state’s instructions, direction, or control. Maddocks shows how Iran’s proxy arrangements typically sit just outside these thresholds: the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is a state organ, but groups such as Hezbollah and the Houthis operate with significant autonomy and without formal legal “empowerment,” complicating attribution on Article 5 grounds.

The study’s most prominent recommendation is to broaden how “empowerment” is interpreted under Article 5. Today, that provision is often read to require empowerment “by the law” of the state—an unrealistic expectation for covert proxy relationships. Maddocks argues this narrow reading “does not accord with the realities of contemporary conflict” and enables states to avoid responsibility simply by withholding formal legal authorization. She proposes recognizing factual authorization indicators—coordination, training, financing, and operational support—as evidence sufficient to treat proxy conduct as performed “on behalf of” the state.

She also urges more robust use of complicity principles (aiding or assisting another actor’s wrongful acts with knowledge of the circumstances) and attention to independent breaches of primary norms (such as the prohibition on the use of force and non-intervention) arising from a state’s support to proxy groups—even when strict attribution fails. These avenues, she argues, can still ground state responsibility for materially enabling unlawful attacks.

The report emphasizes that, absent doctrinal evolution, Tehran and similarly situated states will continue to benefit from plausible deniability. By updating the attribution framework—especially the interpretation of Article 5—to reflect how modern proxy warfare actually operates, Maddocks contends the international community can narrow the legal gray zone that Iran has exploited for decades.