New Study Shows How Global Jihadist Groups Are Defining Their Enemies

A comprehensive study by George Washington University analyzes how jihadist organizations currently frame and prioritize their enemies—from Israel to local governments to the West

Researchers at the George Washington University's Program on Extremism published a new study on February 16th examining how global jihadist organizations construct and prioritize the figure of the "enemy" within their strategic narratives, revealing that al-Qaeda and the Islamic State frame threats, assign blame, and mobilize audiences through starkly different discursive practices centered increasingly on local rather than Western adversaries.

Central to jihadist ideology for decades has been the distinction between the "near enemy"—local governments and regimes—and the "far enemy"—primarily the United States and Western powers—a conceptual framework that has historically shaped strategic priorities, but one that both organizations are now fundamentally reorienting.

The findings, drawn from the TITAN Project (Terrorism Insight Through the Analysis of Narratives), represent one of the most comprehensive empirical assessment of jihadist messaging to date, analyzing a digitized corpus of official audiovisual materials from both organizations’ primary media outlets.

A Meaningful Strategic Realignment

The data paints a striking picture of organizational priorities. For al-Qaeda, nearly 49% of all enemy references in propaganda now target local regimes and governments, compared to just under 28% directed at the United States. This marks a substantial departure from the organization’s historical emphasis on striking American targets globally, a strategy that defined al-Qaeda’s approach following the 1998 establishment of the World Islamic Front for Jihad against the Jews and Crusaders.

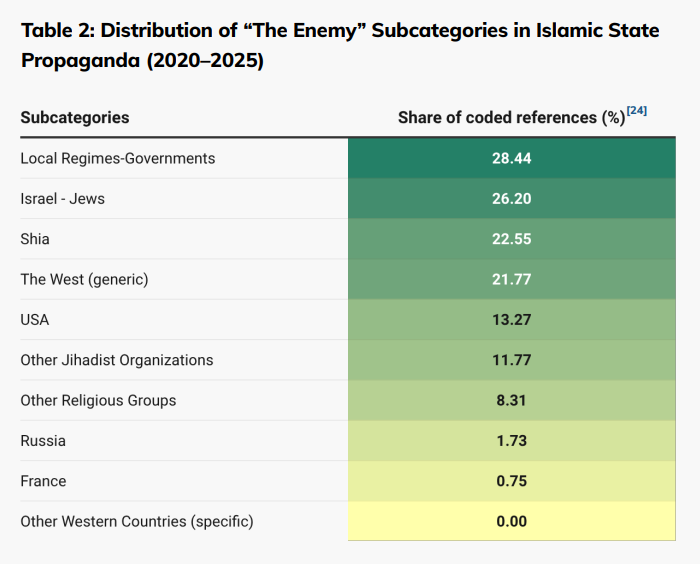

The Islamic State demonstrates an even more pronounced shift away from a far enemy focus. Rather than concentrating on any single enemy category, ISIS distributes its enemy references relatively evenly: 28% target local regimes, 26% focus on Israel-Jews, 23% on Shia populations, and only 13% on the United States directly. This distribution reflects a fundamental difference in how ISIS constructs its enemy landscape compared to al-Qaeda.

Divergent Rhetorical Approaches

Despite both organizations emphasizing the near enemy, the ways they discuss and delegitimize local targets reveal crucial strategic differences. Al-Qaeda maintains what researchers describe as a “strategic-doctrinal logic,” preserving a conceptual separation between near and far enemies while linking them instrumentally in strategy.

The organization frames Arab and Muslim rulers as apostates and Western collaborators—servants of a global order designed to subjugate Muslims—but stops short of calling for their complete annihilation. As a decentralized network operating across multiple theaters, the organization requires flexibility and the ability to build coalitions with local populations. Maintaining analytical distinction between political critique and theological extermination allows affiliated groups to adapt messaging to local contexts while remaining ideologically coherent.

In contrast, the Islamic State employs a “theologically absolutist” approach that collapses all enemies into a single cosmic adversary. ISIS depicts local regimes not merely as misguided or corrupt, but as intrinsically hostile to Islam and therefore subject to eradication.

Notably, the study found that ISIS portrays local rulers as collaborators with Jews and Christians, framing them as traitors who actively assist Western powers in their conflict against Muslims.

ISIS propaganda employs dehumanizing imagery describing regimes and their forces as “shoes” and “dogs” of Americans—language that, as researchers note, erases moral constraints on violence by rendering targets subhuman. Where al-Qaeda uses political and theological critique to delegitimize rulers for mobilization purposes, ISIS weaponizes theology to justify what researchers characterize as exterminationist rhetoric.

The Blurring of Boundaries

The research reveals that the classical near-far enemy dichotomy, which has shaped jihadist strategic debates since the 1990s, remains conceptually important but increasingly blurred in practice. Both organizations simultaneously reference local rulers and their foreign patrons in single propaganda pieces, creating a rhetorical framework in which enemies near and far are presented as parts of an interconnected system of oppression.

This rhetorical fusion serves recruitment purposes. By linking local grievances—corruption, authoritarianism, human rights abuses—to global systems of Western domination, these organizations offer populations a coherent explanation for their suffering and position themselves as the solution. The tactic has proven effective across theaters from Iraq to the Sahel to Southeast Asia.

Three Central Findings

The evidence points to three key findings. First, both al-Qaeda and ISIS have meaningfully reoriented their messaging toward local enemies, a shift that reshapes recruitment strategies by transforming political grievances into religious imperatives.

Second, they employ fundamentally different rhetorical strategies to achieve this reorientation: al-Qaeda maintains a strategic distinction between near and far enemies while linking them as part of a unified system, whereas ISIS collapses all enemies into a single existential threat, fusing theology with explicit calls to violence.

Lastly, while both organizations have clearly prioritized the near enemy, the data suggests this represents a strategic recalibration rather than complete ideological reversal.