Law Professors Warn Federal Court Ruling Enables Universities to Evade Antisemitism Accountability

NYU and UMich law profs challenge Title VI ruling, while a separate analysis by a University of Oregon prof finds that universities can constitutionally discipline faculty advocating violent extremism

Leading law professors from New York University and the University of Michigan have issued a scholarly paper challenging a recent federal court decision that distinguishes between antisemitism and anti-Zionism on college campuses. According to their analysis, the First Circuit's dismissal of Stand with Us v MIT threatens to shield universities from Title VI liability despite documented harassment of Jewish students. In their analysis, Samuel Estreicher of NYU and Zachary D. Fasman of University of Michigan contend that courts are fundamentally misunderstanding civil rights law by requiring proof of discriminatory motive rather than focusing on the harassment's impact on victims.

Meanwhile, University of Oregon professor Ofer Raban argues in another newly-released study that extreme anti-Zionist speech calling for violent destruction of democratic states can cross constitutional boundaries, even under First Amendment protections, when it demonstrates professional unfitness for academic positions.

Courts Apply Wrong Legal Standard to Campus Harassment

In a comprehensive analysis published following the First Circuit’s 2025 ruling in Stand with Us v MIT, NYU law professors Samuel Estreicher and Zachary D. Fasman argue that federal courts are misapplying decades of established hostile environment harassment law. The First Circuit dismissed lawsuits against MIT without allowing pretrial discovery, ruling that months of campus demonstrations and harassment created no liability under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The professors contend this represents a fundamental misunderstanding of discrimination law, according to their analysis. Hostile environment harassment claims do not require proof that harassers intended to harm members of a protected group. Instead, liability turns on whether conduct was unwelcome and offensive to a reasonable person in the victim’s position.

The First Circuit incorrectly concluded that plaintiffs must establish “antisemitic animus” behind protests, dismissing evidence that demonstrators mounted an encampment directly across from Hillel, the campus Jewish center. The court reasoned that protesters may have chosen the location for its “prominent location and preferred terrain for tents” rather than proximity to Jewish students.

“This is entirely the wrong analysis,” the authors write. Supreme Court precedent established that harassment liability focuses on the effect of conduct on victimized students, not the subjective motivation of harassers.

Universities Required to Take Prompt Action

The scholars emphasize that once universities have notice of a hostile environment, they face a legal duty to take reasonable steps to eliminate it. The Department of Justice’s 2025 Title VI Legal Manual states unequivocally that universities violate Title VI when they fail to take “prompt and effective steps reasonably calculated to end the harassment, eliminate the hostile environment, prevent its recurrence, and address its effects.”

MIT’s response—allowing five months of campus disruption before acting—falls far short of this standard, according to the paper. Complaints detail Jewish students physically prevented from attending classes, professors resigning due to harassment, and students told to use back entrances on the anniversary of Kristallnacht for their safety.

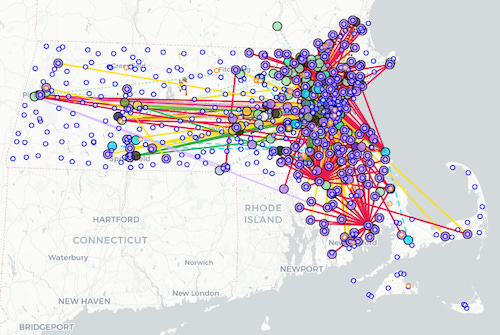

The Sussman v MIT complaint states that student groups distributed flyers with links to the allegedly Iran-tied “Mapping Project” listing local Jewish businesses with instructions to “reveal the local entities and networks that enact devastation, so we can dismantle them.” MIT’s president acknowledged the project “promotes antisemitism” but allegedly took no action.

Estreicher and Fasman pose a pointed hypothetical: Would an institutional response taking five months to stop racial misconduct against Black students ever be considered “prompt and effective” as a matter of law? Courts would never tolerate such delays if protesters created “whites only” encampments, prevented Black students from walking freely on campus, or distributed lists of Black businesses urging students to “dismantle” them, the authors argue.

Anti-Zionism Often Functions as Disguised Antisemitism

The professors address the contentious relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. While acknowledging that opposition to Israeli policies doesn’t automatically constitute antisemitism, they state that “being ‘anti-Zionist’ in today’s parlance is often little more than antisemitism dressed in slightly different clothing.”

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of antisemitism—adopted by 46 countries including the United States, 37 state governments including Massachusetts, and numerous universities—classifies as antisemitic the denial of Jewish people’s right to self-determination and holding Jews collectively responsible for Israel’s actions. MIT protests began October 8, one day after the October 7 massacre and before Israel took military action in Gaza, suggesting protesters celebrated rather than protested military operations.

According to the analysis, the First Circuit’s conclusion that anti-Zionist conduct cannot be antisemitic because not all Jews are Zionists misses the legal mark entirely. Discrimination law has never required that conduct offend all members of a protected group to be actionable. Playing misogynistic music in workplaces constitutes sex harassment even if some women aren’t offended.

A 2024 survey by the American Jewish Committee (AJC) show 81% of American Jews consider caring about Israel important to their Jewish identity. The proper test asks whether conduct would offend “a reasonable person in the plaintiff’s position,” not whether it offends every Jew on campus.

Kentucky Professor’s Suspension Passes Constitutional Test

In a separate analysis of public employee speech rights, University of Oregon law professor Ofer Raban examines the suspension of University of Kentucky law professor Ramsi Woodcock. The case provides a stark example of how anti-Zionist rhetoric can cross legal boundaries even under First Amendment protections.

Woodcock has called for violent destruction of Israel, described October 7 terrorist attacks as “legitimate,” and and advocated for the establishment of an international coalition to declare war against the Jewish state.

Raban argues that under the Pickering-Connick balancing test governing public employee speech, Woodcock’s suspension passes constitutional muster. The test weighs employees’ interests in speaking on public concerns against government employers’ interests in maintaining functional work environments and ensuring employee suitability.

Academic freedom protections require that scholarship abide by standards of truth, rigor, and accuracy, according to the paper. Raban asserts that Woodcock’s writings fail these standards through factual lies, historical misrepresentations, and absence of serious legal analysis. His work constitutes “political activism masquerading as legal scholarship” that diminishes public interest in hearing purported expert opinion.

Raban notes that Woodcock’s positions fall “beyond the pale” of legitimate political discourse by American standards. Not one of 535 members of Congress endorses violent destruction of democratic states or justification of terrorism. Speech calling for extreme unlawful violence and justifying crimes against humanity ranks low on constitutional protection scales when weighed against universities’ interests in denying platforms, funding, and authority to disseminate violent ideologies.

Importantly, Raban states that “Woodcock’s anti-Zionism is morally disqualifying even if we avoid calling it antisemitic” because it advocates violent destruction of a democratic state and justifies terrorism—issues that transcend political viewpoint and enter the realm of professional unfitness.

Universities Can and Must Enforce Policies

Both papers emphasize that context fundamentally matters in evaluating harassment claims. Antisemitic incidents increased 900% over the past decade, with campuses experiencing the fastest growth in 2024, according to Anti-Defamation League data.

Estreicher and Fasman reject arguments that universities lack sufficient control to comply with Title VI obligations. Recent examples from Dartmouth and the University of Florida demonstrate that institutions can promptly enforce time, place, and manner restrictions without violating free speech principles.

UCLA’s failure to allow Jewish students full access to campus for one week led to a federal injunction and $6 million settlement in Frankel v. Regents of the University of California. The professors conclude that universities must enforce their own policies protecting all students’ ability to access educational opportunities.

This free essay is Absolutely Critical reading if you want to grasp the full scope of this unfolding dynamic and the centuries-long historical pattern driving it. For the deep-dive analysis backed by historical sources, doctrinal explanations, current demographic data, specific incidents, and documented "receipts" (including references to Pew projections, Europol reports, Global Terrorism Index, and primary historical chronicles), read the full piece here:

It lays out, without apology, how taqiyya-enabled deception combined with strategic mass migration is advancing a long-term project toward global Sharia dominance, and why ignoring it risks the irreversible erosion of Western (and all non-Islamic) freedoms. Wake-up call material.

https://sleuthfox.substack.com/p/the-trojan-horse-how-americas-education